The recent passing of Pope Francis reminded me of last year’s Conclave, the Oscar-nominated thriller portraying the ancient ritual for the election of the pope. I have no gift for writing reviews, so here’s one if you are unfamiliar with the story, and another recommending the film as “sinfully entertaining.” It may have been making political claims, indeed one clip suggests that the pope that passes in the beginning is meant to be Francis. But the political theorizing isn’t very interesting or nuanced. I would agree with the general consensus that the film is well-made and intriguing. But I felt strongly that it was made by someone who doesn’t know any Catholics. It became obvious to me that an outsider cannot comprehend what it means for Christ to be present in his Church.

It is for this reason that the film is bleak. The cardinals inhabit lifeless, stony halls of residence, and are cared for by sour religious sisters who glare at the clergy they serve. The conclave’s dean, Cardinal Lawrence, fuels undeniable tension throughout the film. He is a figure at once laughed at for his “naïveté” when he admits that he really believes the cardinals are doing the work of God; yet still helplessly open about his troubling doubts for the future of the Church. The film offers almost no relief until the election of an intersex pope, which is even more depressing to Catholics, who understand why such an event is an impossibility, not to mention fantastical and strange. In other words, Conclave’s depiction alienated me. It doesn’t resemble the Church I love.

Hollywood narrates what anyone can see from the outside: a curmudgeonly institution haunted by the weakness of its members, on the verge of collapse since time immemorial. The portrayal forces the usual questions: how can the Church overcome bad actors? How can we trust that God works in a human institution, one burgeoning with sin, regret, power struggles, and, importantly, doubt? It is important that Cardinal Lawrence asks as much in a homily critical to the film: where is the pope that will be open to uncertainty? The pope that doubts? He is in effect asking: who can know God?

The answer: those who pray.

In 1935, Romano Guardini, one of the most influential Catholic scholars of the 20th century (especially to Popes Benedict and Francis) published a brief treatise entitled, The Spirit of the Liturgy. In it he makes an important distinction about two elements of the Church. Guardini calls the “work” of the Church the aspects (such as canon law) pertaining to the necessary management of people. My contention is that the film artlessly reduces the Church to this serious, governing body, while Guardini contrasts the “work” with his subject: the inherently “playful” liturgy. Worship makes up the lived, revelatory half of knowing God, he says. It’s the half absent in Conclave.

Guardini warns that “[g]rave and earnest people,” as he puts it, “tend to experience a peculiar difficulty where the liturgy is concerned.” Trapped in an obsession to find clarity, Cardinal Lawrence becomes increasingly unfamiliar with the divine heuristic. No longer seeking recourse in the truly informative heart of Christianity—which is worship— he finds himself in a crisis of faith. His path is typical, since the film shows how he, his predecessor, and most other cardinals, have lost confidence that God will work through or overcome human weakness. They lobby, campaign, and dig up the dirt on each other, just like politicians do. They rarely pray.

According to Guardini, those who participate in the liturgy engage in something decidedly other than the work of a governing body. The liturgy is purposeless: an enjoyment of God. The liturgy is wasting time with God, much as we do with friends. The “grave and serious”, concerned only with the efficient, productive operation of the Church, and the calculated articulation of truth1, cannot comprehend the bliss of the liturgy’s playfulness. To the rattled dean leading the college of cardinals, it would be like a foreign language. But that is because it is supernatural. In the liturgy, we are not agents but lovers.

To say that the liturgy is purposeless is to insist that it isn’t for the sake of anything else. It is for us. Guardini says when a child plays he does so to “develop and realize itself more fully.” When we pray, too, we find in the liturgy the “capture and expression of our nature.” Participation in the liturgy is not really about being a better person or about knowing more about our faith, although these indirect ends may occur. It is about fulfilling a creative need, a coming-to-be that happens when we worship God the way he taught us to.

It’s dangerous to interpret praise of God as something with a higher purpose, even, as I mentioned in another essay, if you think that the end is that God will reward you. When we do so in the Church we become like the proverbially grave and serious: Michal, who, seeing David dance before the ark of the covenant, derided him2, the pharisees, whose obsession with form and righteousness make them miss the heart of Christ’s message3, or even Judas, who was appalled at Mary Magdalene’s waste of precious oil when she anointed the feet of her Lord4. This grave mien characterizes the whole film of Conclave because it depicts a soulless Church— no beacon or model that means anything to real people.

Why God is Hidden

One of the most common issues I hear with regard to God and the Faith is questioning where he is when people suffer, or why he doesn’t answer our prayers. We are programmed to imagine that a good God always makes us happy. We think in human, contractual terms about a divine lover. We cannot comprehend the disparity of our worlds.

Prayer, which is what transpires in the liturgy, is God’s continual self-revelation to his Church. The liturgy is instructive not in the sense that we go to learn certain lessons, but where we meet the “opportunity of realizing (our) fundamental essence.” It is where we go to see ourselves as God sees us. Guardini provides a helpful analogy: in the spiritual exercises of St. Ignatius a person is meant to meditate on certain realities to learn specific lessons. This practice can be likened to a gymnasium, where devices target particular muscles. But the liturgy is more like a forest: fodder for unstructured play and all that we will learn about our bodies and nature by spending lots of time there.

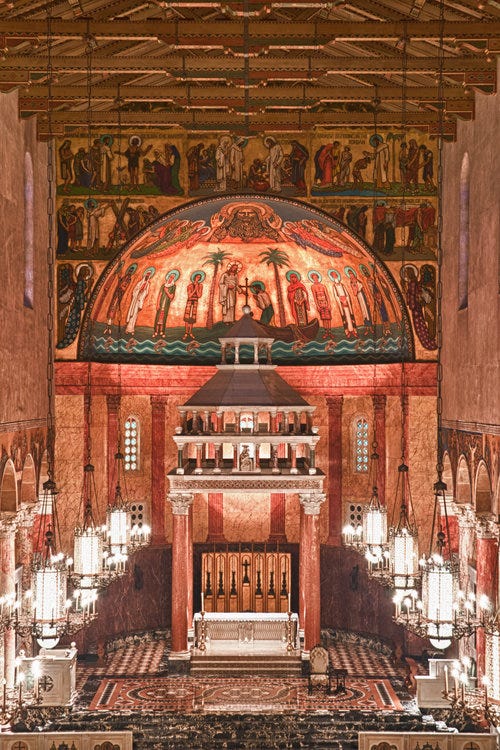

We learn in the liturgy, too, the way we learn from a work of art. According to Guardini, art should “clothe in clear and genuine form the essence of things and the inner life of the human artist.” A piece of art is not a class, and there is no syllabus, yet the sensory engagement in music, a short story, or a painting may more profoundly illuminate us than anyone’s words will. When we worship we participate in the wisdom of God, which is to say that it is less that we can comprehend him and more that we become familiar with him. We can say of the liturgy what we can claim of art: art reveals, it doesn’t instruct.

In short, the liturgy is not memorizing the Catechism but developing certainty that we are made to be children of God. Attendance may not make us verbally articulate defenders of the faith, but there are other parts of the tradition to do that. The liturgy is a fountain of youth, a regenerative, intuitive knowing God that inspires love and confidence in him. As is traditionally inscribed on the steps of the altar: Introibo ad altare Deum, ad Deum qui laetificat iuventutem meum: “I will enter into the altar of God, to God who gives joy to my youth.” Love of God enlivens us.

The significance of commitment to the liturgical life of the Church (whether it be mass, personal recitation of the office, or even praying the Our Father) is that these are our principle means of communicating with God. We do so through Christ, who is no set of rules, nor a textbook, nor a feeling, but a person. Like every person we know well, it is because we spend time together, share ourselves, and become vulnerable. Like everything we know really well, it is with the fullness of our being, the savoring of sweet association, and characterized by unshakable confidence.

The film is a depressing internal look at the Church because it depicts a tomb, not a living body. The college of cardinals are rudderless, acting not in unison or with common aim because they see only half the Church. The pivotal crisis of faith results from believing we control a divine institution. We do not control but cooperate with God. The Church requires both the structured form of her hierarchy, as well as the wondering, receptive revelation of liturgical prayer, to meet Him.

The Church must and does articulate truth clearly. But this necessity falls under the work side; an obsession with which makes one miss the forest for the trees

2 Sam 6:14-22

Jn 8:1-11

Jn 12: 1-4